Last week I briefly suggested for you to practice mining memories from your childhood if you want to write for children or teens. This is something I do naturally, as a lifelong journaler. I’m used to writing everything down in order to make sense of something that has happened to me or a way I feel or events happening in the world. Or sometimes even to make a decision that’s plaguing me. And I’m used to returning to those pages years later in reflection on where I’ve been and where I’m at. Writing is the best tool I have ever been given and much of my own craft has been developed over a lifetime of putting pen to page, or fingers to keyboard. But if you didn’t grow up writing or writing from a young perspective is new to you, it doesn’t mean you can’t create a great story. There are plenty of authors who never wrote for kids (or anyone) and then suddenly did. This is the joy of writing: it’s a craft you can start honing at any age and you improve upon for the rest of your life.

So mining memories. How does one do this?

I think the best way for me to explain my process is to give you a recent example of applying an actual memory to my writing. To be clear, mining memories doesn’t always mean you’re incorporating an autobiographical moment in your fiction. Sometimes it’s the emotions that you need to apply to a particular scene, but not the exact event. What was it like when you got stitches for the first time? Apply that to your character’s first ER visit. Or scored your first goal in soccer? Apply that to your character winning a science fair award. Or kissed a girl? Apply that to your character’s most embarrassing moment, or first love. Uncover all the little moments that we hardly think about in our day-to-day lives anymore, but were big moments when we were young. If you can reach back to how you felt in that moment, you’ll be able to better write from that age perspective in any fictional setting.

Back to memories. I’m working on (albeit exceptionally slow for me) a ghost story that has quite a bit of autobiographical ties, minus the ghost, which has required me to delve into memory much deeper than my earlier middle grade work. Lydia’s (the protagonist) father has just been sent to a treatment facility for alcoholics, for not the first time, and her life is somewhat crumbling around her. She hasn’t done homework for weeks, she gets benched from the swim team, she’s depressed, and she’s frustrated with the cycle of abuse that keeps happening in her home while she feels completely invisible and powerless. The ghost shows up and while it’s scary at first, it ends up being a fantastic distraction from the rest of her life. It’s been a more challenging writing process for me 1: because my own life has been in massive upheaval over the last year and it’s greatly affected my ability to draft new work, and 2: because so much of Lydia’s story is my story.

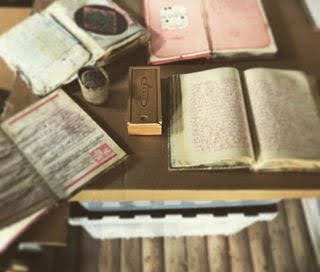

The really hard stuff aside, here is an example of a tiny memory I had to think back on in order to channel a feeling into my protagonist. Lydia is called into her guidance counselor’s office for failing classes and is offered a tutor. Lydia is offended because she’s smart, she’s just not doing any work. When I was in sixth grade, this was me. I remember my English teacher used to have this system of “excusable excuses”. He had little slips of paper that had “name, date, homework assignment, reason for not completing, your signature, and then boxes that he would check as “excused” or “not excused” reasons. Then he would sign them and return them back to you. It was a small way of keeping us accountable and a tangible record of where we stood with our excuses. I had a lot of these slips of paper. I don’t remember how many excuses you were allowed. Probably three. I had an entire collection tucked in a journal only lost because of a fire I had several years ago. I kept those silly papers because I was so ashamed of myself when I was twelve for not doing my work. I tried to come up with the most mature and rational sounding excuses. “Personal problems”. “Lack of sleep.” “Left my textbook at school.” I don’t remember if any of them were specifically true, but in a way they were all true. They were tiny scraps of proof of what was going on in my home–alcoholism, abuse, and a lot of related chaos.

Unlike Lydia’s timeline, I never saw a guidance counselor and no one called home in 1988. The forensics of my sixth grade year were all mine to hide and stow away between pages of my diary that I knew no one would ever find. No one would ever read my journals, because, frankly, I don’t think anyone was paying that close attention. What I remembered the most, however, was how much I hated not getting my work done–I loved learning, if not school all the time–and yet I was not able to complete anything. I was full of shame.

As an adult, there is no shame, only compassion for that twelve year old who was just trying to survive. And a deeper understanding of when life is chaos, finishing anything is very difficult.

But I need to make myself remember that twelve year old feeling. Then I take that shame and infuse it into poor Lydia, while also taking great care to execute a scene in which the reader can feel Lydia’s shame and understand it, but also have compassion for her, seeing clues that her life circumstances are prohibiting her from being a good student, even if they do not have similar experiences.

Here’s the rough draft version of that scene:

I cross my feet and stare at my lap for what feels like forever, until Ms. Sharon, in charge of kids M-Z, steps out and invites me into her office.

“How are you, Lydia?” she asks as I shut the door behind me.

“Fine.”

She folds her hands on her desk, and half frowns, half smiles, that look that says I like you, but I’d like you better if you did XYZ.

“I’m going to cut right to the chase. Is there anything you want to tell me about? Anything going on that’s prevented you from doing your homework for the last two months?”

My insides clench. I kind of guessed this is what this would be about, but being called out so directly makes me feel like an idiot. I shake my head.

“You have no reason for not doing any work?” She sounds kind, like maybe she’d understand if I told her, but I’m so embarrassed I can’t speak, let alone tell her the truth.

“Because your grades in Language Arts, Science, and history seem to be saying otherwise and math isn’t far behind. And math has always been your best subject.” She sorts through some papers on her desk, holds up one of my pre-algebra quizzes with a bright red D scrawled across the top.

“I forgot to study for that one.” I lie. Well, it wasn’t entirely a lie. I didn’t study. But not because I forgot. That night Mom and Dad were screaming so loud I ended up sneaking out of the house and walking to the park where I sat on the swings for hours, texting Jill and just waiting for the all-clear. Thinking back, I guess I could have brought my book and studied on the swings instead of wasting my time texting.

“And what about this essay?” She looks at my sorry excuse for an essay. “This was supposed to be two pages and you have four sentences.”

I slouch in my seat.

“Honey, I’m not trying to make you feel bad. I just want you to see how out of control this has gotten. Your teachers have told me they’ve all spoken to you several times, and talked to your mom, and there’s been no improvement. I’m going to have to contact home again.”

My face gets hot and my eyes burn, but I refuse to cry. “Please don’t.”

She looks concerned. “Would tutoring help? We can set up something for you after school instead. Some of the high school students--”

I shake my head. I don’t need a tutor. I understand my classes, I just didn’t do the work.

“Unfortunately, if you don’t have anything to add to this conversation, I am going to have to call your mom. And you can’t remain on the swim team until your grades are back up to C’s.”

She stacks all the papers up nice and neat, slides them in a folder and tucks it in her desk. I imagine it to be the drawer of Epic Fails. Where all kids like me who just can’t manage to keep things straight, were hidden, out of sight. Invisible.

I only watch her move about the office, saying nothing, and accept my fate. What can I do anyway? It’s way too much work for me to try to catch up at this point. She said two months, but I think that was a gift; it’s been much longer than that since I started making up reasons.

Forgot my book.

Lost the study guide.

Got sick.

Mom made me go to an Alateen meeting.

I’ve run out of excuses. The best I can do is hope to just get through seventh grade without failing anything else.

“I’ll do better,” is all I can squeak out before I leave Ms. Sharon’s office.

Did I manage to mine the emotion AND instill compassion for Lydia? Every reader is their own judge of that, but I think it’s getting there. Judge lightly, it’s a first draft after all. :)

Now go mine some memories/emotions and write them down. Especially if you don’t still have your childhood journals or excuses for not doing homework. These moments, no matter how little they might seem now, are gold mines for your writing, be it from the young perspective or the adult. Take the time to document your experiences, emotions, thoughts. Make lists if it’s easier than paragraphs. If you want to write, you must be willing and able to examine your own life or you’ll have a much harder time examining a character’s.

At least that’s this writer’s theory.

Thanks for sharing, Jess. I am a huge believer in mining memories for my fiction, and am amazed constantly over the variety of memory elements I am able to access. Cheers!